This blog post outlines a recent paper which I worked on with my fantastic collaborators Joel Dyer, Fabio Zennaro, Yorgos Felekis, Theo Damoulas, Anisoara Calinescu and Mike Wooldridge. This work is set to be published at NeurIPS 2024 - check out the full paper here!

ABMs and the Need for Surrogates

As micro-data becomes increasingly available, agent-based modelling becomes an increasingly attractive framework to model and analyse complex systems. Since agent-based models (ABMs) simulate systems at the agent level, they allow us to investigate exceptionally fine-grained policy interventions. Additionally, unlike machine learning models such as neural networks, one can readily incorporate domain knowledge that may not be represented explicitly in data.

Unfortunately ABMs are often computationally expensive to run and difficult to integrate into machine learning pipelines. Moreover, they often produce complex individual-level outputs that are difficult to analyse. In practice, we often want to reason about a complex system at the macro-level, in terms of its emergent properties.

This motivates us to pursue surrogate models which

- are computationally cheap to run

- easy to integrate into existing ML pipelines

- and reason at the macro-level.

ABMs as Causal Models

An ABM implcitly defines a structural causal model (SCM) that specifies how agents interact with each other and the environment. Unfortunately, we rarely have explicit access to this SCM, and even if we did, it would be tremendously large. This is in part why we encounter the issues described above with ABMs, and why reasoning causally about ABMs is difficult. Our lives would be made far easier if we had access to a simple causal surrogate model that is interventionally consistent with the original ABM. This line of thought leads naturally to causal abstraction theory!

Causal Abstraction Theory

Causal abstraction theory aims to relate two structural causal models defined over different sets of variables. There are many frameworks for causal abstraction. In this work we use \(\tau\)-\(\omega\) abstraction. Investigating the formal connections between different abstraction frameworks constitutes an interesting research direction, and you should check another of Fabio’s papers if you are curious about it!

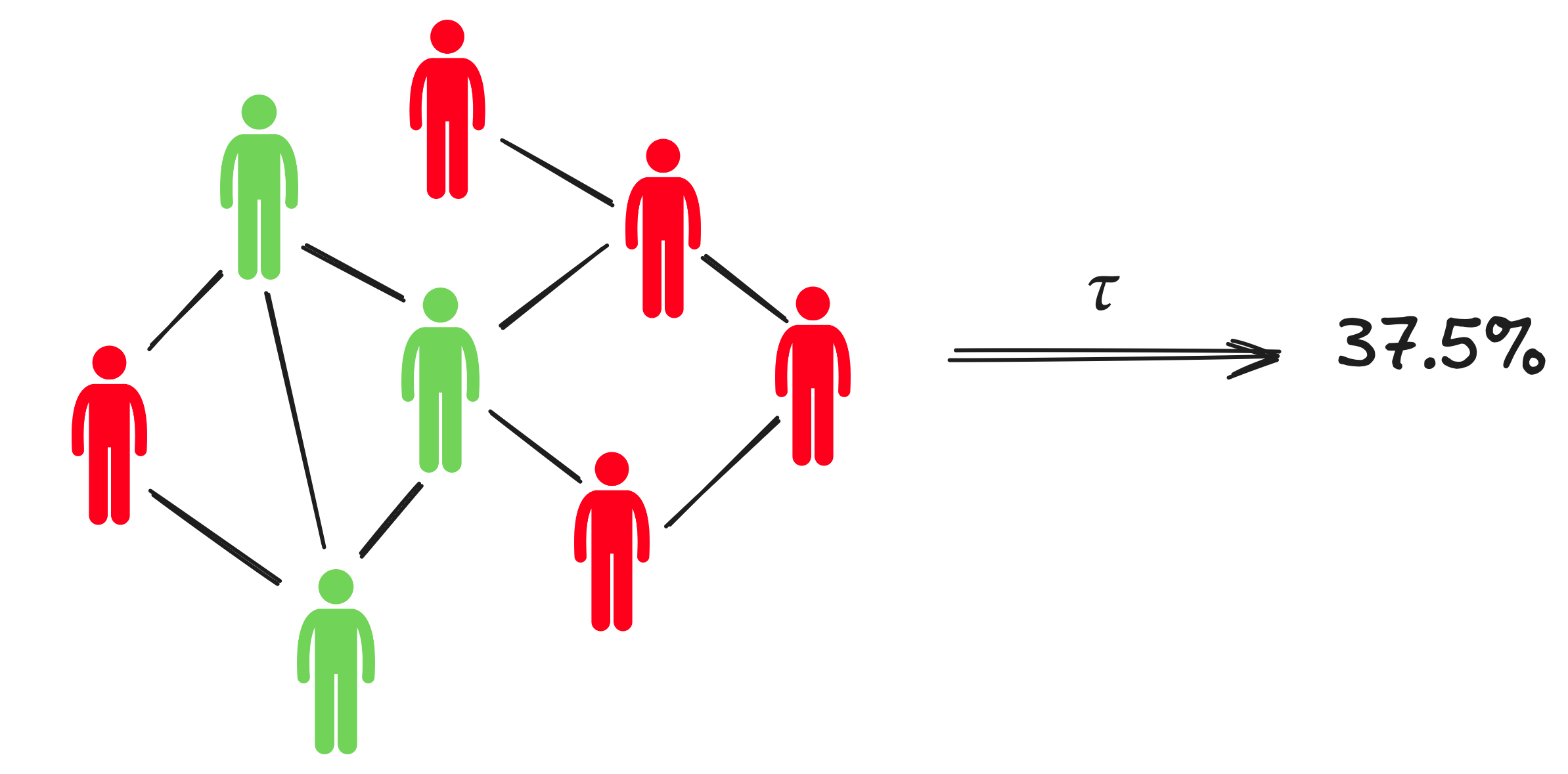

Consider two SCMs; a base model \(\mathcal{M}\), and an abstract model \(\mathcal{M}^{\prime}\). You can think of \(\mathcal{M}\) as an ABM and \(\mathcal{M}^{\prime}\) as a simpler surrogate model. A \((\tau, \omega)\)-abstraction is a pair of maps \(\tau\) and \(\omega\). \(\tau\) maps variable assignments in the base model \(\mathcal{M}\) to variable assignments in the abstract model \(\mathcal{M}^{\prime}\). For instance, consider an epidemilogical ABM that tracks the infection status of individual citizens through time via a set of binary variables, and a simple ODE simulator that tracks only the total fraction of infected individuals through time. In this case, it is natural to let \(\tau\) simply count the number of infected individuals in the ABM on each time step. Note that this gives rise to a corresponding variable assignment in the ODE model.

Generally speaking, \(\tau\) should map the microstates of the ABM to macroscopic emergent properties that an expert would like to reason in terms of. We will assume from hereon that \(\tau\) is some fixed map that a domain expert has chosen.

Meanwhile, \(\omega\) maps interventions in the base model to interventions in the abstract model. Consider the previous epidemiological example. Our ABM may allow us to perform lockdown interventions to limit disease spread. In contrast, it is unclear what a lockdown intervention would look like in the ODE model as it does not simulate at the individual level. \(\omega\) is responsible for telling us what intervention in the ODE model corresponds to a lockdown. Unlike \(\tau\), it may be difficult for a domain expert to naturally specify an \(\omega\) map. We will come back to this issue soon!

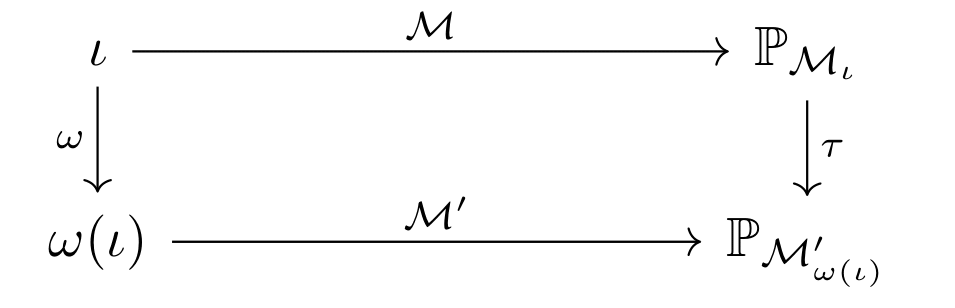

Interventional Consistency

What makes a good abstraction? Say we want to observe a macroscopic output associated with an intervention \(\iota\) in the ABM. We have two options. We could map \(\iota\) to its corresponding abstract intervention \(\omega(\iota)\) and apply it in the surrogate \(\mathcal{M}^{\prime}\) to obtain a macroscopic output directly. On the other hand, we could simulate \(\iota\) directly via \(\mathcal{M}\) to obtain a microscopic output and lift it to the macroscopic level via \(\tau\). Logically, we want both of these procedures to produce the same output. In other words, abstracting then intervening should be the same as intervening then abstracting! More formally, we want the following commutative diagram to hold for any possible base intervention \(\iota\)!

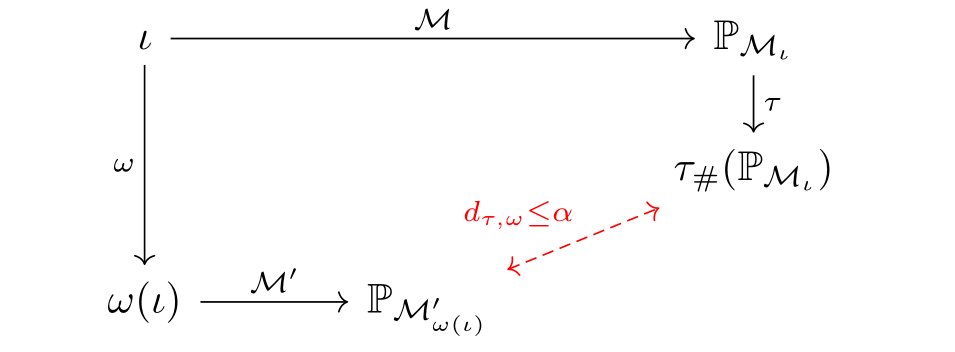

In the diagram above, \(\mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}_{\iota}}\) and \(\mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}^{\prime}_{\omega(\iota)}}\) correspond to the interventional distributions associated with \(\iota\) and \(\omega(\iota)\) respectively. Commutativity is quite a stringent goal and one we are unlikely to achieve exactly for every intervention \(\iota\). That is, whichever surrogate model and intervention map \(\omega\) we choose, the interventional distribution attained by intervening then abstracting may differ from the interventional distribution attained by abstracting then intervening. Our goal should be to minimise the distance between these distributions as much as possible!

This naturally leads use to the definition of abstraction error:

\[d_{\tau, \omega}(\mathcal{M}, \mathcal{M}^{\prime}) = \mathbb{E}_{\iota \sim \eta} \left[ d\left(\tau_{\#} (\mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}_{\iota}}) ,\, \mathbb{P}_{\mathcal{M}^{\prime}_{\omega(\iota)}}\right)\right].\]Here, \(\eta\) is a distribution over base interventions, whilst \(d\) is a divergence between probability distributions. In words, the abstraction error measures the average difference between abstracting then intervening versus intervening then abstracting. The abstraction error depends heavily on the interventional distribution \(\eta\), which should be carefully chosen by a domain expert to reflect the interventions they care most about.

Learning an Abstraction

Recall that our goal was to learn surrogate models for ABMs. The abstraction error presents a natural metric for us to optimise. By setting the divergence \(d\) to the KL-divergence, we may jointly learn both a parameterised surrogate model and a parameterised intervention map that minimises the abstraction error.

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:our_loss} \phi^{\star}, \psi^{\star} % ) = %\in \arg\min_{\phi \in \Phi, \psi \in \Psi}d_{\tau, \omega^{\phi}}(\mathcal{M}, \mathcal{M}^{\psi}). \end{equation}\]Here, \(\phi\) corresponds to parameters of the intervention map \(\omega\) whilst \(\psi\) corresponds to parameters of the surrogate model \(\mathcal{M}^{\psi}\). If we are careful in our choice of parameter families we can solve the above problem via stochastic gradient descent. With this in mind, let \(q_{\iota}(\cdot \; ; \; \psi, \phi)\) denote the density of the interventional distribution produced by the surrogate \(\mathcal{M}^{\psi}\) under the intervention \(\omega^{\phi}(\iota)\). By choosing both parameter families so that the densities \(q_{\iota}(\cdot \; ; \; \psi, \phi)\) are tractable and differentiable with respect to \(\phi\) and \(\psi\), we can form Monte Carlo gradient estimates for the abstraction error using ABM outputs \(\mathbf{y}_{b}\) generated by forward-simulating interventions \(\iota_{b}\) sampled from \(\eta\):

\[\nabla_{\phi,\psi}\, d_{\tau,\omega^{\phi}}(\mathcal{M}, \mathcal{M}^{\psi}) \approx \frac{1}{B} \sum_{b=1}^B - \nabla_{\phi,\psi} \log q_{\iota_{b}}(\mathbf{y}_{b} \; ; \; \psi, \phi).\]Note that we do not need to forward simulate the ABM during training, as only evaluations of the surrogate densities \(q_{\iota}(\cdot \; ; \; \psi, \phi)\) are required. In other words, a batch of interventions \(\iota_{b} \sim \eta\) can be sampled and forward-simulated offline prior to surrogate training.

Note that the method we propose is not the only way to learn an abstraction. In fact, Yorgos recently published a paper outlining an alternative approach based in optimal transport at CLEAR this year!

The Importance of Interventional Data

To highlight the efficacy of our approach we conduct experiments using an SIR ABM designed to model epidemics. In short, this ABM consists of individuals connected by a graph. Individuals can be susceptible (S), infected (I) or recovered (R). On each time step, infected individuals have some fixed probability of recovering, whilst susceptible individuals have some probability of becoming infected based on how many of their neighbours are infected. We construct a set of neural network surrogates which sequentially process outputs from the classical SIR ODE model that models the fraction of susceptible, infected and recovered individuals through time.

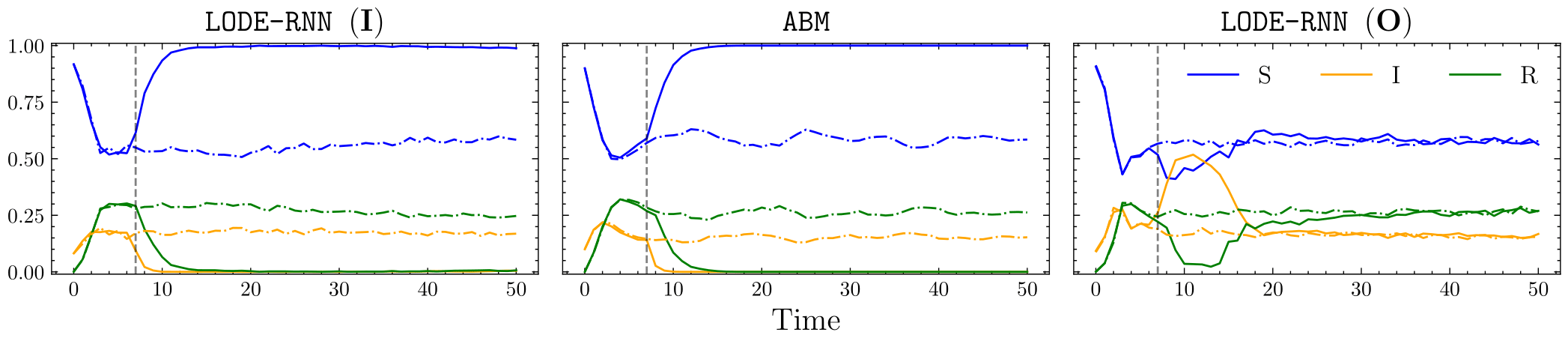

For base interventions, we consider lockdowns that correspond to severing connections in the underlying graph of the SIR ABM for a fixed duration. For our surrogates, we consider interventions that directly edit the parameters of the underlying SIR ODE model for fixed durations. The image below shows three plots. Dot-dashed lines correspond to observational simulations where no intervention was performed, whilst solid lines correspond to simulations where an intervention was performed. The central plot shows a simulation of the SIR ABM, where a lockdown \(\iota\) (vertical line) was performed. The left plot shows a simulation of a surrgate model trained using the stochastic gradient scheme from the previous section, where the intervention \(\omega^{\phi}(\iota)\) was performed. Note that the surrogate matches the ABM very well! The right plot shows a similar simulation but for a surrogate trained with purely observational ABM simulations where no lockdowns were performed. As expected, this surrogate cannot replicate the effect of a lockdown in the ABM.

For more details about our approach, check out the full paper!